‘Reckless’ Underpayments: The $4.695 Million Dollar Issue

- Grace Brunton-Makeham

- May 21, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: May 28, 2025

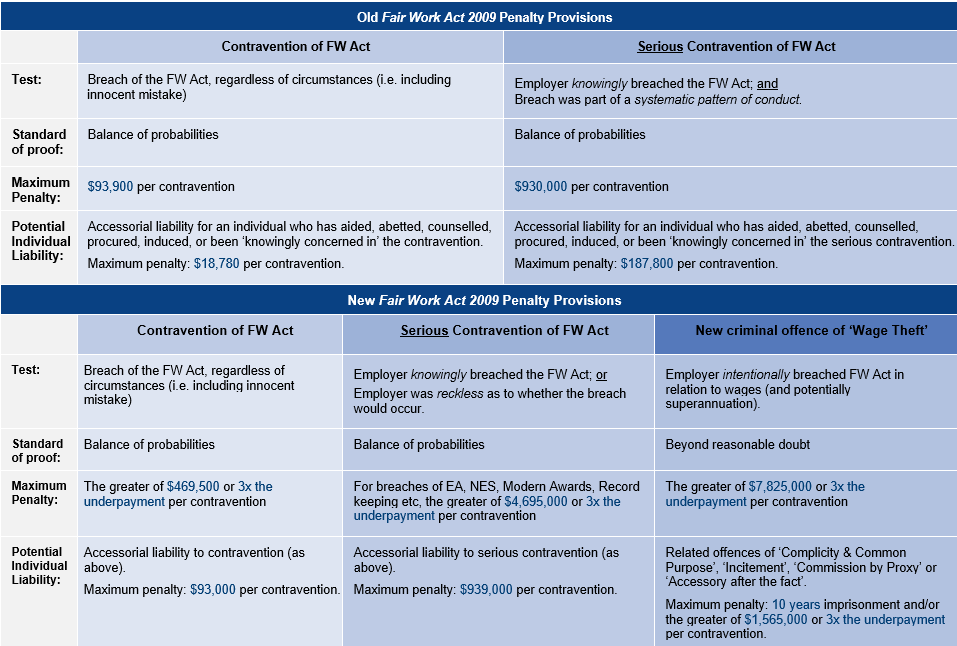

The Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FWA) underwent significant changes in 2023 and 2024. While the headlines at the time went to “wage theft” and the new criminal offences, less headline grabbing changes were made to the ‘serious contraventions’ provision of the FWA. In particular, the new test of ‘reckless’ underpayments, together with a significant increase to penalties (now the greater of $4.695 million or 3 x the underpayment per contravention).

This new recklessness test is where the greatest level of practical risk may exist for businesses - particularly those that have not had a detailed assessment of their payroll systems, processes and capability recently.

The Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) has also recently released its ‘Payroll Remediation Program Guide’. While primarily addressing the FWO’s views on what a remediation program should cover, within it lies clues for employers on managing future risk from allegations of reckless underpayments.

This article explores the interpretation and risks of these changes, the FWO expectations, and what employers may want to think about for assurance and risk management.

Summary & Key Takeaways

‘Serious contraventions’ of the FWA attract 10x the usual penalties.

The FWA has recently been amended to:

Lower the bar for what is considered a ‘serious contravention’ – it now includes ‘recklessness’; and

Increased the penalties for serious contraventions x 5 – it is now the greater of $4.695 million or 3 x the underpayment per contravention.

The new ‘recklessness’ test effectively asks whether the employer knew their actions/failures to act could carry a risk of non-compliance and took that risk anyway?

Given the complexity involved in pay compliance, if an employer does not have adequate payroll oversight at a governance level, or appropriate systems and processes to identify and prevent issues and manage risk, in the event underpayments are identified it may leave the employer open to allegations it was engaged in ‘serious contraventions’ of the FWA.

Boards, risk committees and senior management should be considering what level of oversight and assurance they have over their payroll and employment compliance risks.

If you are interested in understanding more about payroll assurance and managing employment compliance risks, please contact us.

For a more detailed analysis of the recklessness test and its potential impacts on employers, read more below.

Changes to Substantive Law and Penalties

The Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Legislation[1], amended the FWA to (among other things):

increase the penalties for contraventions and ‘serious contraventions’ of the FWA x 5;

significantly lower the bar for ‘serious contraventions’ by introducing a ‘recklessness’ test; and

introduce a criminal offence for intentional wage theft.

The ‘Recklessness’ Test: Lowering the Bar for Serious Contraventions

Arguably the most practical risk for businesses relates to the changes made to the ‘serious contraventions’ provision. The threshold has shifted from requiring conduct that was both "knowing and systematic" to conduct that is "knowing or reckless." This represents a fundamental departure.

This is important for businesses for three key reasons. First, the recklessness standard appreciably expands the scope of potential serious contraventions (along with related significant penalties). Second, it shifts focus to circumstances where risk management failures could constitute a serious contravention. Third, it in effect aligns FWO enforcement tools with modern corporate governance expectations around risk awareness and mitigation.

What does it mean to be ‘Reckless’?

Section 557A(2) of the FWA states that a person (or entity) is reckless as to whether a contravention would occur if:

(a) the person is aware of a substantial risk that the contravention would occur; and

(b) having regard to the circumstances known to the person, it is unjustifiable to take the risk.

Subjective and Objective Elements

This definition of recklessness mirrors the concept of recklessness in the Commonwealth Criminal Code[2] and contains both subjective and objective elements.

Whilst there is no caselaw on the FWA provision yet, commentary on the equivalent Commonwealth Criminal Code provision notes that while the person or entity must have been subjectively aware of a risk of some kind, assessing whether it was ‘substantial’ involves asking if a reasonable observer would have characterised it in this way. The ‘reasonable observer’:

…may be in possession of more information than the [person] and will usually be endowed with far better judgement about risks...[3]

Accordingly, a person or entity may be treated as having been aware of a ‘substantial’ risk even though they themselves viewed the risk as minor.[4]

‘Substantial’ Risk

As to what a reasonable observer would determine is a ‘substantial’ risk, the issue is not clear cut. However, it has been established that ‘substantial’ is not necessarily a risk which is more likely than not[5].

‘Unjustifiable’

As to whether it was ‘unjustifiable’ for a person to take a risk in the circumstances known to them, the courts are likely to use an objective standard of what an ordinary, reasonable person would consider justifiable in those specific circumstances.

For instance, in New South Wales, the assessment of whether it was ‘reasonable’[6] for a person to take a risk in the circumstances has been described as requiring consideration of a range of factors including the ‘magnitude of the risk … along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the [person] may have'.[7]

Knowledge of a Corporate Entity

Lastly, there is the question of attribution of knowledge in the context of a corporate entity. That is, how does a body corporate know something? Section 792(2) of the FWA states that where it necessary to establish a ‘state of mind’ (including knowledge) of a body corporate, it is enough to show that the conduct was engaged in by an officer, employee, agent of the body corporate acting within the scope of their actual or apparent authority (an ‘official’) and that that official had that state of mind.

Key Takeaway

The recklessness test essentially asks:

Did the employer (or their officers/employees/agents) know their actions/failures to act would carry even a minor risk of non-compliance?

Would a 'reasonable person' view the actual risk of non-compliance as ‘substantial’?

Would a reasonable person view taking the risk as ‘justifiable’ given the magnitude of the risk and the employer's particular circumstances at the time (e.g. expense, difficulty, conflicting responsibilities)?

In our view, given:

the significant public attention on corporate underpayments and “wage theft”, including continual media reporting of underpayment issues;

the well-known complexity of payroll systems, modern awards and enterprise agreements; and

the FWO’s position that it won’t accept ‘general statements of assurance’ (see more below),

if a business fails to implement adequate oversight of payroll at a governance level, including conducting regular audits of payroll compliance and addressing risk areas, it could be difficult to prove it was not ‘reckless’ in the event underpayments are identified.

Lessons From the Past

Interestingly, the previous ‘serious contravention’ definition ("knowing and systemic") was never tested at law, despite operating from 2017 to 2024. Most FWO prosecutions under s557A involved smaller operators who admitted liability. The only significant corporate case that proceeded to a penalty was Fair Work Ombudsman v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2024] FCA 81 and in that matter the respondent, CBA, also admitted liability (albeit after protracted negotiations regarding the Statement of Agreed Facts).

Notably however, CBA paid $10.6 million in penalties on approximately $16 million of underpayments - a substantial ratio even under the old penalty regime (and noting the penalties have increased 5-fold since then).

The reformed 'serious contraventions' definition of ‘recklessness’, together with the significantly increased penalties, provides the FWO with an even more powerful tool against employers suffering system and process failures. ‘Recklessness’ - a significantly lower bar - will likely capture organisations that have poor oversight and inadequate risk management.

FWO’s Expectations

While focused on remediation programs, the recently released ‘FWO Payroll Remediation Program Guide’ (the Guide) gives some strong clues over the FWO’s expectations for forward assurance and the new law. For example, it "won't accept general statements of assurance… …in the absence of a willingness to provide appropriate supporting evidence."

While the Guide is not the law, it identifies and focuses on future risk management of payroll and wage compliance - noting a baseline of being able to show the following have been considered and addressed:

assurance and audit risk management,

culture and governance,

systems and technology, and

people and processes.

What should your business do?

With all that in mind, boards and risk committees should be critically asking:

What evidence of payroll compliance have we seen and reviewed?

What specific risk management frameworks govern wage compliance?

How frequently does management look at and report on payroll risks to governance committees?

What systems and process exist to identify and prevent issues?

In turn, management should be able to demonstrate that it is looking at risk in a measured and methodical way i.e. proactive risk identification, it reviews its systems and capability regularly, and addresses uplift needed to support a culture of wage compliance.

This is commentary published by Makeham Flaherty for general information purposes only. This should not be relied on as specific advice. You should seek your own legal and other advice for any question, or for any specific situation or proposal, before making any final decision. The content also is subject to change. A person listed may not be admitted as a lawyer in all States and Territories.

Makeham Flaherty 2025.

[1] Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Act 2023 (Cth) and Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes No. 2) Act 2024 (Cth)

[2] Explanatory Memorandum to Fair Work Legislation Amendment (Closing Loopholes) Bill [3] The Commonwealth Criminal Code: Guide for Practitioners (2nd ed, 2002) Pt 2.2, div 5.4-A, 73

[4] Victorian Law Reform Commission ‘Recklessness: Issues Paper’ (2023) 9, 35

[5] The Commonwealth Criminal Code: Guide for Practitioners (2nd ed, 2002) Pt 2.2, div 5.4-A, 73–75.

[6] The NSW equivalent of ‘justifiable’.

[7] Aubrey v R (2017) CLR, 329 [49] (Kiefel CJ, Keane, Nettle and Edelman JJ).

![[Part 1] Academic Workloads: Issues and Considerations for Enterprise Bargaining and Wage Compliance](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/d3ff2a_de3f6dc4c9c8486c8d8d402711296056~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_651,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/d3ff2a_de3f6dc4c9c8486c8d8d402711296056~mv2.png)

Comments